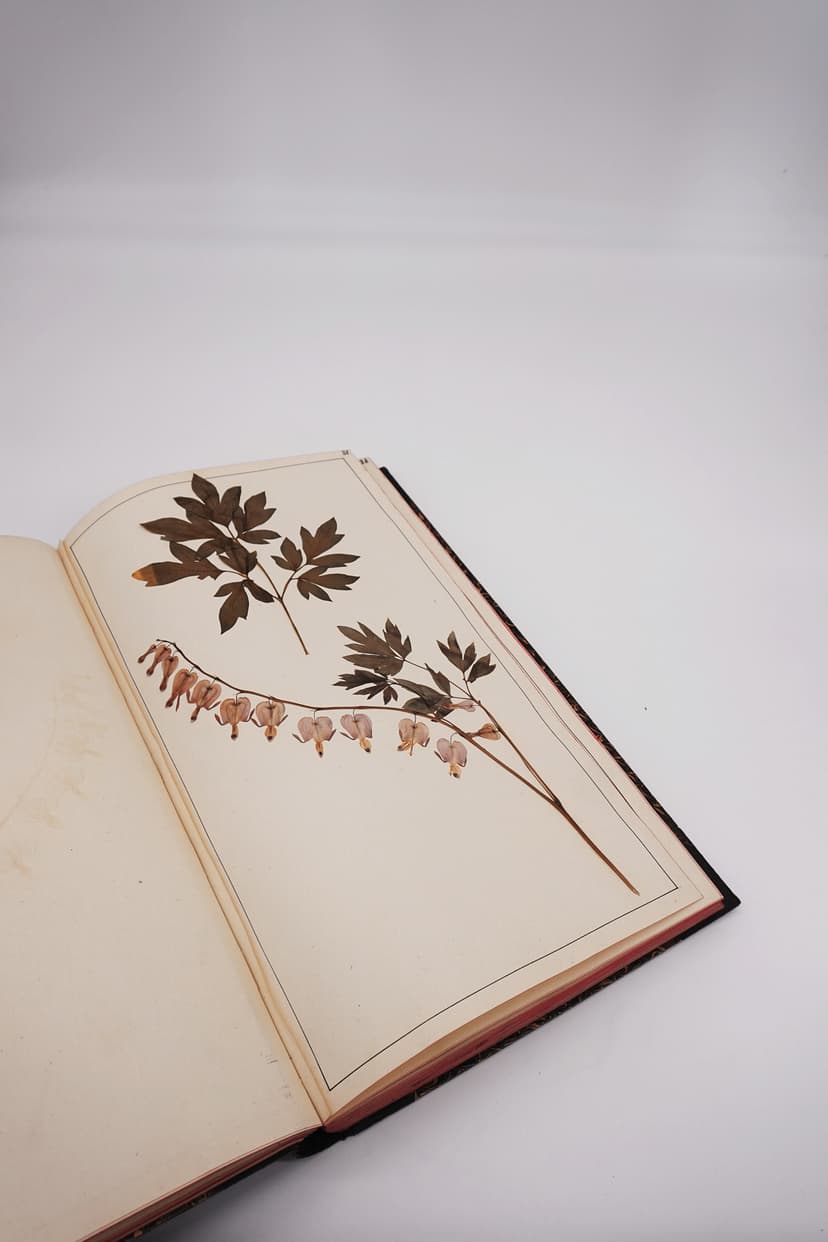

I discovered it when my grandmother died in 1988: my great-great-grandfather's herbarium. My family history stretches back to the 17th century. I have an infinite amount of material at home, countless exchanges of correspondence, and so many interesting objects, but no one in my family has yet gotten around to delving deeply into our ancestral history. But this herbarium immediately captivated me. It's a large book, not the usual portrait format. And it had this beautiful handwriting. I was curious. How could the flowers stay beautiful for so long? I found plants in the book that actually still grow in my garden. The vine, for example. It's my great-great-grandfather's. Or the yew. It's so mighty and tall that you can see it from the Jacobi Cemetery. I'll have to have it trimmed back because I'm afraid it'll topple over in the next storm. I stand before this tree with humility. When you plant a tree, you're doing something for future generations. It was also my great-great-grandfather who gave me the decisive impetus to reorient my life. With his herbarium, I entered a new chapter in my life.

After graduating, I returned to Lübeck and started my own business here. I worked as a fashion designer for 20 years. When my mother died, I thought I wanted to do something different. When a mother dies, it changes everything. I changed, too. It was a profound turning point. I thought about what I can do, what do I want? Can I capture time? I had truly learned the hard way that time is the most precious commodity. I knew I wanted to make something others didn't have. I like to eat. And I have a pretty good sense of smell and taste. I can be very persistent. I can experiment for a long time. And what do I have? I have a garden. Is there any material more beautiful than flowers?

I tried it for six months. Every day. I hadn't learned it. And I was laughed at. Only my daughter believed in me. Back then, flowers were still very new in culinary terms. It was unusual to see a flower on a salad every now and then in an upscale restaurant. I wanted to try preserving them. After six months, I was at the point where I thought: Okay, this way they can go out into the big wide world. My daughter helped me with the marketing. At the end of March, when everything was in full bloom, winter hit, so I really had nothing left to process. I was on the verge of ruin. I thought another product line could help me, something everyone liked; chocolate would be the solution. Then, like a gift from heaven, an inquiry from Dior came. They had a new fragrance and wanted candied rose petals for the presentation, which would taste exactly like the fragrance smelled. But it was March, and there were no roses anywhere. So I had some flown in from organic gardeners in Israel to the wholesale market in Hamburg. I only had a description of the scent. It was truly like looking for a needle in a haystack, but I had nothing to lose. I was on the brink of collapse. So I ran. I drove to the wholesale market in Hamburg at 3 a.m., processed the roses, sent them to the German headquarters in Düsseldorf, and received the feedback: Great, but it needs to be rosier. I just thought: I'm going to collapse. They couldn't have known what an effort it was. I tried it three times. After the third time, I had the contract and supplied 2,000 perfumeries with roses. Then I wrote the best invoice of my life. I could have bought a nice car with it, but I bought a device that could melt chocolate at different temperatures. That was the launch pad for the wonderful world of chocolate. And I have to admit: success is fun. I've certainly lacked many things in this life, but not courage.

I always had such incredible respect for the things my great-great-grandfather made. He was a gifted wood turner, even master of the guild. He worked with such intricate craftsmanship. As a child, I was never allowed to touch things. In my work, I also deal with intricate things: I candied edible flowers. That's where things come full circle. Nowadays, it's something special to want to preserve things. Back then, that was normal. Furniture was for life. My daughter said something a while ago that made me laugh: "You don't have a single piece from Ikea, do you?" It's true. I want to continue my great-great-grandfather's tradition. This house is not a gilded cage. It's an anchor. It's nice when you walk through that big, heavy front door into the house. Then the door closes, and it's quiet. It's such a good feeling of security. Especially at Christmas time, when the crowds stream past the house, it's good to come home, or, for example, to be able to walk into the garden on Sunday mornings when all the church bells ring. It's the most peaceful place in the world. I use this house as a tool to live in the moment.

But I also respect the responsibility and the tasks that come with such an old house. Sometimes I don't even know how I'll manage it. It's actually much too big for one person. But as we all know, you grow with your challenges.

I have two large portraits of my great-grandfather and his wife, Mariechen. They hang in one of the rooms where I work. When I'm candying flowers and tinning them, I sometimes look at the portrait and think, oh yes, if we could have met, we would have liked each other. We could have enjoyed each other's work. I would have given them a piece of chocolate. I always want the best, as much of it as possible, to share with good people.