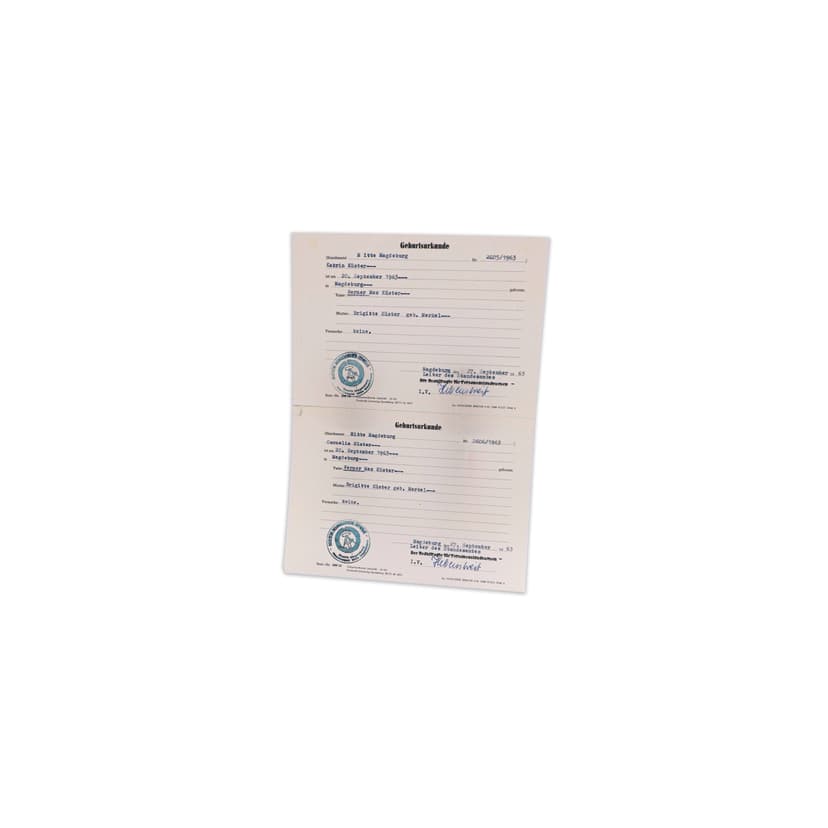

Katrin was born together with her twin sister Cornelia in Magdeburg. But to this day, there has been no trace of Cornelia. Shortly after her birth, she is said to have suffocated and died as a premature baby. The parents never saw their supposedly dead child. No grave, no evidence. Nothing. After the fall of the Wall, Katrin discovered articles in the newspaper about missing children in the GDR. Again and again, more and more frequently, she read about people searching for their siblings, their children, who apparently disappeared without a trace in the GDR. Their parents were citizens loyal to the regime. Shortly after Cornelia's death, her father, 22, a young police trainee, had to fill out a form: waiving an autopsy, the grave, and filing a complaint against the nurse who had last cared for the premature baby. During the GDR era, an autopsy was mandatory for deceased children weighing 1000 grams or more. Katrin and her twin sister each weighed about 1700 grams. "Well, if I find out that your father had something to do with this... yes, then I'd get a divorce right now," her mother said. Katrin suspects that the disappearance might have something to do with it: "Because he went to police academy, and they might have put pressure on him because of that." It later turns out that her father was just as clueless as Katrin's mother. "Growing up in the GDR, you didn't really question anything you were told. There was really nothing to question because you never got any information." Thus, Katrin's parents didn't question the death of their second child until their own daughter confronted them. This began a major family process of coming to terms with the situation. The stories that Katrin reads in articles and hears in conversations encourage her to take matters into her own hands and investigate. This begins a search that lasts for years and continues to this day. With her mother's permission, Katrin turns to a private detective. She visits Stasi representatives, the women's clinic, the city hospital, the library, the city archives, she undergoes genetic testing, goes to university, and joins the Association of Stolen Children in the GDR. But she doesn't find much. The thought that there might be someone else in the family she's never seen haunts Katrin. Before she goes on vacation, she dreams of meeting her sister there: "As I walked through the city... I said to myself: You're stupid. What's going on in your head?" How can it be that a child disappears without a trace in the GDR? In the GDR, she didn't dare to question anything. Katrin did what she was told and lived by it. Many years later, she found the courage to ask questions. In conversation, she talks about her efforts as if it were a given. But it isn't at all. How many families, parents, siblings, and children live in Germany who don't deal with their past, or don't even want to? Katrin doesn't give up. The idea that her other half could reappear sometime, somewhere, gives her the greatest strength: "I'm definitely not giving up. I'm still hoping for a coincidence that will bring me something."