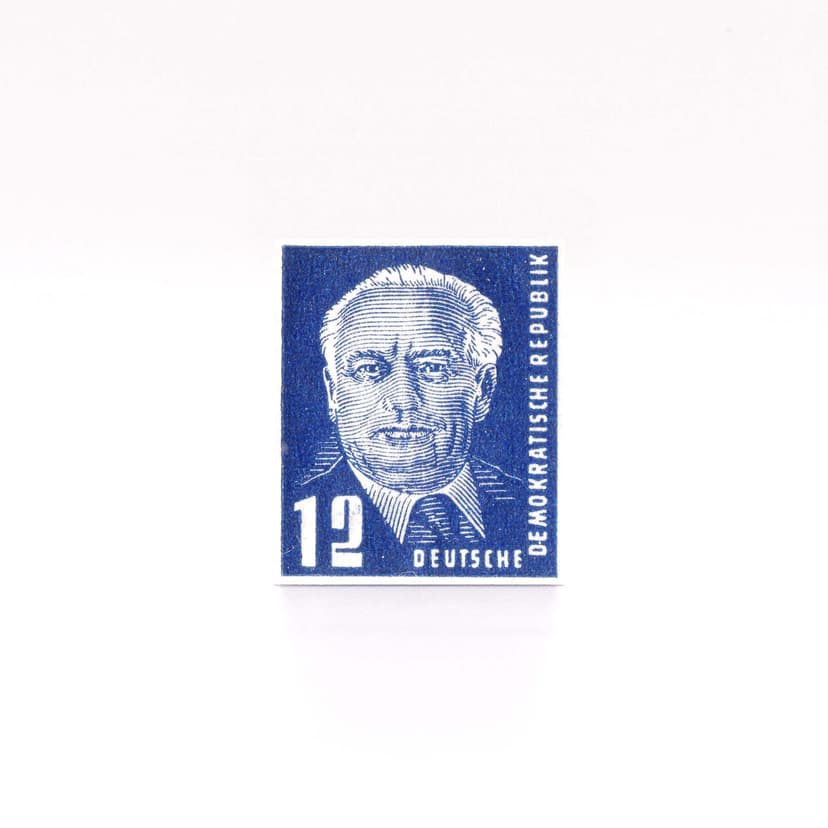

At the end of the 1980s, I worked in IT organization at VEB Textima-Elektronik. A large circuit center was to be built to produce the GDR's first 1-megabit memory. Construction was in full swing, the buildings were already up, and the utilities (air, water, electricity) were connected. My job and that of my colleagues was to formalize the business processes and represent them in simple programs for accounting and statistical purposes. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, all of this was no longer of any use. Megabit memory had long been available on the global market, and our "programs" would hardly have elicited a smile from anyone. In July 1990, part of the workforce was put on short-time work (0 hours), my colleague and I were among them. I found that quite unfair – why not our colleagues? But there wasn't much time for complaining. My husband had set up a small project with colleagues and students at Chemnitz University of Technology and was now seizing the opportunity to start his own business. Bulgarian friends organized a large quantity of the then-popular Rosenthaler Kadarka, which had been sold as a "buckware" during the GDR era, and with the help of family and friends, we tried to sell the wine to department stores and restaurants. The proceeds formed part of the company's "share capital." The secretary's first salaries were deducted from my salary. We had two children, ages 5 and 8, who needed to be looked after. As I write this, I can't understand why I didn't panic back then. On the contrary, I was able to enjoy the summer with the children and finally had time for them. The quick release into short-time work and, as of July 1, 1991, unemployment benefited me for my career reorientation. I was interested in banking, as it had naturally been neglected during my studies, and I was free to choose my desired further training – to become a banker. I was curious about how the new society worked and was able to truly see and seize this change as an opportunity. After completing my one-year apprenticeship, I initially applied to several banks without success – I was already in my early 30s (!) and had two children (!). Full-time employment under these conditions was beyond the imagination of most HR professionals. Ultimately, I landed a position at a leasing company and remained in the industry until I retired. The fall of communism was a time of awakening for me, full of new discoveries and experiences. We were enthusiastic supporters of Gorbachev's policy of openness, and for a long time, I believed in the possibility of building a humane socialism. Through many conversations with colleagues about the events of autumn 1989, it slowly dawned on me that this was a grave mistake. I wasn't one of those who took to the streets to demonstrate their opinions – on the contrary, I spent October 7, 1989, with my family at my parents' house in the village to protect the children. Nevertheless, I experienced the fall of communism as a liberation, as if a heavy burden had been lifted from my shoulders. I was certainly also lucky: The management of Textimaelektronik GmbH took great care of the workforce's needs. The social compensation plan was implemented despite significant difficulties. I felt I was treated fairly and decently. The time was clearly not yet ripe to build a truly new, more humane society. The perceived material deprivation needed to be compensated for, and the new freedom to travel needed to be experienced. My hope for the future is that more and more people will be able to find inner peace; only then will we succeed in living together with compassion and mutual respect.